In California, immigrants are a driving force in our culture and economy. Immigrants are key to what makes California what it is. Yet, a negative stigma remains of many of the immigrants that inhabit not only our state but the country as a whole.

Aydinaneth Ortiz is a photographer whose series, Hija de tu Madre, focuses on migrant mothers and their daughters.

An alumna of Cerritos College, Ortiz’s series is currently being displayed at the Cerritos Alumni Art Exhibition. She’s also currently a professor at Cerritos as well, teaching photography.

Regarding the origins of the series, Ortiz said, “It really started with myself and with my mother and sister. I was really thinking about how we were represented in the media during that time. We had Trump as our president, and he had all these negative things to say about immigrants. This is a way of combating that and showing that we’re actually strong and viable.”

Traditionally, the phrase “hija de tu madre” has a negative connotation. When Ortiz decided to name her series that, she noted that it was an intentional decision.

“It’s a way of embracing that we are like our mothers, whether we like it or not, with the good and the bad. There was a bit of humor with that title and thought… It’s more about saying ‘We’re not from here, but we are an important part of the country now.’ Our mothers made us who we are. That’s where it stems from,” said Ortiz.

Hija de tu Madre is only one of her projects. Ortiz has a wide array of projects that are deeply personal to her and revolve around many of her personal traumas and experiences.

For Ortiz, these projects allowed her to feel a catharsis that was much needed.

“When I started at Cerritos College, photography was my drive to work through issues I was having at home, but during that time I didn’t want to deal with those issues at home. I guess I wasn’t ready. It was more like… my escape. Photography was my way out of this thinking in my mind…. It really started as ‘I want to make a pretty picture. I want to make the best picture I possibly can.’ I transferred to UCLA for my undergrad… when I was there my brother passed away. That really changed things for me. I could no longer hide in my work, I felt like I needed to tackle it head on. It was a very cathartic process… I had all these emotions, but because I was confronting it, it really helped me mourn and move forward,” said Ortiz.

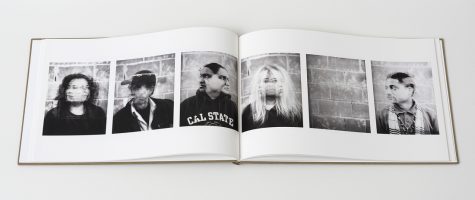

La Condicion de la Familia was one of the projects that helped her work through these feelings. It’s an artist’s book revolving around her family and the experiences that Ortiz felt after her brother passed away.

In an exhibition catalogue for the artist’s book written by the director of the Pomona College’s Museum of Art, Kathleen Stewart Howe, Howe describes the work as “a photography of intimate connections casually rendered, to explore and mediate a family tragedy”.

“La Condicion de la Familia helped me realize that I wasn’t alone with the feeling of loss. I wasn’t alone with having a family member with a mental health condition. I didn’t know that until I put myself out there. There was some comfort in knowing that it wasn’t just me,” said Ortiz.

Not Alone was another project that Ortiz worked on following her brother’s passing. The project consisted of a series of beautiful landscapes. Upon close inspection, one can notice a silhouette in each of the landscapes.

According to Ortiz, these silhouettes were meant to represent her deceased brother.

“’Not Alone’ was made when my brother passed away… I just kept hearing people say ‘Siempre VA Estar Contigo’; he’s always going to be with you and at the time when you’re feeling that loss, it’s almost not enough. So, I thought ‘What if I bring him with me?’. Those images were places that we had been together and places that I had never been to personally. I inserted my brother into them, and it’s a silhouette of the last image I ever took of him with my cellphone. It was my way of putting him in there, and having him present with me,” said Ortiz.

Many of her projects also revolve around her neighborhood and the culture that surrounded her as she grew up.

A Portrait of my Neighborhood is a look into Ortiz’s life as a resident of Long Beach.

“I wanted to document what I felt was an impactful and strong place to live… Some of these images show places that no longer exist. Some of the buildings have been torn down or they’re dramatically changing over time. It’s kind of recording what it used to be. A big part of it is documenting who lives there, and who inhabits this place. What I love about my neighborhood is that there’s a range of different cultures that live there. I want to highlight my neighborhood,” said Ortiz.

Todos Somos Familia is a project that Ortiz started when she’d visit Tijuana. In her car, while waiting to cross the border, she’d often see these vendors who were working. In this project, she captures many of the working men and women who she describes as having a familial relationship.

“I realized that there was this relationship that was a little bit detached just by the nature of me being in the car waiting to cross. So, I decided to get off one time, and start taking pictures. I would go back and give them a print copy of the photo I took of them. I realized how much of a family they all were together,” said Ortiz regarding her inspiration on the project.

Much of Ortiz’s work revolves around confronting the issues that many considered taboo at the time she began to enter the field. Her goal is to make a discussion surrounding these issues more common and allowing people to tackle these issues, knowing that there is someone out there who has felt the same pain that she’s felt.

“I think now, at least more than when I started these projects, people are more willing to talk about mental health and other issues. I’m grateful that we’ve moved to a place where we can talk about these topics more openly. When I started these projects, I didn’t see that. Maybe it was already happening, but I wasn’t aware of it,” said Ortiz.

Whether it’s highlighting the migrant mothers who make shape and influence their children, covering the issues and pain that come with one’s passing or highlighting the wide array of cultures and people that make Long Beach what it is, what Ortiz ultimately wants is to start a discussion.

“I think I’m at a point where I’m ready to deal with not only the heartaches that I’ve dealt with in my life, but also embrace the happy things that we do. The things that my culture does and participates in” said Ortiz.