Imagine for a moment living in five different countries before the age of 18. Prottyuth “Chapal” Barua doesn’t have to imagine it.

From nation to nation, a young Barua was forced to follow her father’s job route, which leaped from Europe to Asia and finally, to North America.

“Our first posting was in Poland,” Barua said. “I don’t really remember much about that because I was an infant, then we moved to Germany and we lived there for about five and a half to six years. I remember very vividly I went to a private British school…”

Barua was born in Poland. Her father works for the embassy of Bangladesh and with that comes being stationed in European countries.

He would be repositioned every five to six years, and once he moved, his two daughters and wife followed.

From Germany at the age of five, to her family’s country of Bangladesh and from Italy, to a life of asylum in the United States, Barua remains passionate about her education at Cerritos College despite her life as a refugee.

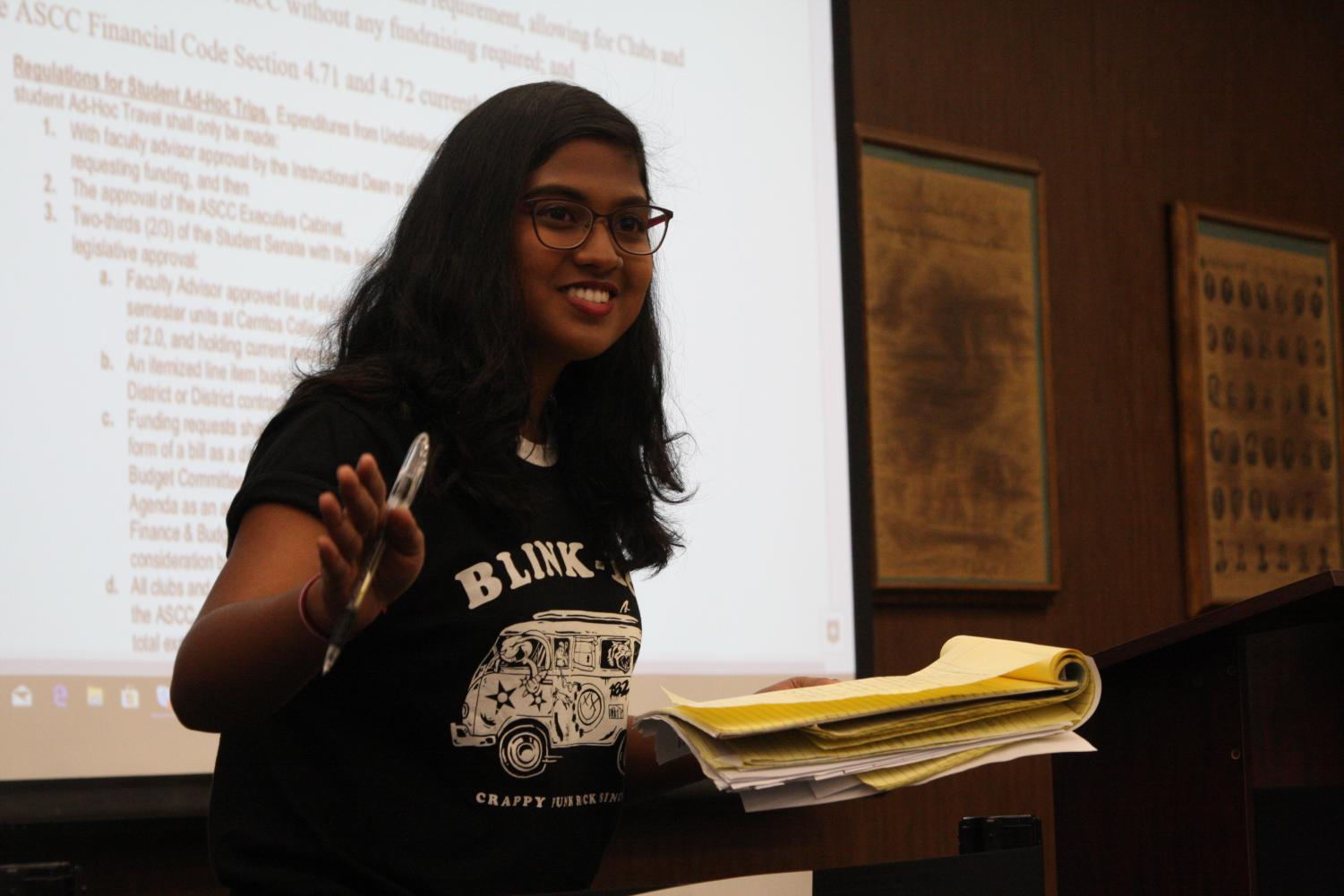

Prottyuth “Chapal” Barua speaking at ASCC senate meeting. Chapel as been apart of student government and recently served her final semester.

Her first vivid memory of schooling was in Germany. She moved there with her family at the age of five.

“I lived in Berlin for about five and half, six years. This was back in 2002. And I learned the language. It was pretty cool,” she said. “I remember there were three students, myself, another Indian girl and another Scottish guy.

“So, there was this teacher she would put a picnic blanket outside and the three of us would sit down and the teacher would just point at random things. She would say the German word for them. I remember that being one of my first German classes, just going out into the wilderness and pointing out different things,” Barua said.

Barua was able to get the majority of her classes in English, but living in Germany she had to pick up the language.

She would go down to the playground when all the kids where there as the kids spoke German, she was able to pick up the language as if it was her own.

Barua said she caught so quickly that the school transferred her to the advanced German class where it was taught as a mother tongue.

This isn’t the only time she picked up languages on her path of education.

“In order to keep the education consistent my parents thought it would be better for me to study in a private English institution instead of going into the public sector,” she said.

In between times her father would be repositioned, they would go to Bangladesh where they’d stay in the capital city of Bangladesh, Dhaka.

Both her parents are Bengalis. When moving back to Bangladesh to await her father’s next task, she lived with persecution.

Another ethnic group in the capital known as the Biharis would harass her family.

“I was pretty young, but what my mom was telling me is when we moved from Germany to Bangladesh we moved into a neighborhood that had a really different ethnic group. So, for that you need to know a little bit of history of Bangladesh,” she said.

“Bangladesh went through a lot of civil wars and there are a lot of ethnic groups there and there’s a certain ethnic group that associated with Pakinstaines. And if you know the history of Bangladesh we kind of don’t like each other, so they kind of stayed in Bangladesh due to war and were not able to go back to Pakistan, they don’t share a border so it’s hard to go back.

She continued: “So, this ethnic group, they’re called the Bihari, they stayed in Bangladesh and they lived in a particular place in the capital city of Bangladesh in Dhaka. And my parents ended up buying a house there.”

Barua said all sorts of things happened including bangs on their front door at night and frequent water and gas shutdowns on purpose.

“It continued for a good year and a half until we were sick and tired of it and we moved out,” she said.

Because of this, Chapal and her family hesitated to go back to the capital of Bangladesh, Dhaka. So after her time in Italy, her mom decided to visit the United States with a tourist visa.

“When I moved here I came with a visa, but I came with a tourist visa. And we weren’t initially thinking about staying here, my mom just wanted to check out the place,” Barua said. “She wanted to see America before going back to Bangladesh. And she really liked it here, so she ended up staying…overstaying her visa. And it was a federal [offense], you’re breaking the law by doing so.

“But it wasn’t safe to go back to Bangladesh anymore,” Barua said. “So, my mom, sister and I, the three of us, we filed a case to stay as asylum, refugees.”

Coming to the states in 2014, Barua made her case to the courts to seek asylum.

During the waiting process she feared for her life. She feared the courts denying her case, which would force her to go back to Bangladesh where persecution awaits her and her family.

“So, in the beginning it was terrifying, because once you turn in your case you don’t hear from them for a long time and during that period you don’t have any papers, you don’t really have any valid document at this point,” she said. “You’re just stuck so it becomes terrifying. Like, even police scare you at this point.”

Her case finally made it to court and gave her a bit of hope.

“But, soon after that our court case went to court and they said ‘well you can just stay here and you can work’ so I have a social security and a work permit. But when I come to school I’m still considered undocumented, because I’m not a permanent resident or a U.S citizen,” Barua said.

Despite her status, Barua is about to graduate Cerritos College in the spring of 2018. She’s going to continue her education by going to medical school. He dream school is UCLA, where she would like to study human biology.

She went on to speak of the distinction between her fight for citizenship and those who have applied for the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals program.

“I feel like my fear is different. Different from other undocumented students because…I don’t even qualify, I don’t have DACA. I didn’t move here when I was like 2, I was a full grown adult,” she said. “The American government knows I’m here, but I’m still subjected to removal, because if my court case doesn’t pass, they can just say ‘we’re going to deny your case, your going to have to go home.’”

Home, of course, would be Bangladesh.

Barua, however, wishes the path to citizenship was easier, she desires American citizenship. “If immigration were easier here and to do it the right way only took an exam, I would do it,” she said.